We think that the old white men zealously prosecuting and hearing this case in the alleged ‘public interest’ – an interest that remarkably coincides with the dying interests of a narrow wealthy white establishment – need to consider this statement very carefully. And then, maybe, they need to consider whether defending some shitty old monument to wealth, slavery, white power and the British establishment is really the best use they can make of their rather sad, empty, self-important little lives:

“My father was born in Barbados in 1934. He arrived in England in 1957 at the age of 23. He was recruited by London Transport in Bridgetown, Barbados. He was required to sign a one year contract with a penalty of £95 if he did not complete the full year.

My family name, Daniel, is my father’s name. It is a plantation name. My father carries this name as my grandfather’s grandfather was an enslaved person ‘owned’ by Thomas Daniel.

Thomas Daniel laid claim to my grandfather’s grandfather. He was the son and main heir of Thomas Daniel, the fifth largest sugar importer into Bristol before 1800. The younger Thomas Daniel became an elected member of Bristol Common Council in 1785 at the age of 23 and the Sheriff of Bristol between 1786 and 1787. In 1796 Thomas Daniel became an Alderman, a position he held for the next 30 years. In 1797 he became Mayor of Bristol. He had a role in the council for over 50 years in total.

Thomas Daniel was a member and Master of the Society of Merchant Venturers (SMV) and a founding member of Bristol’s West India Committee, which was specifically set up to petition parliament against the abolition of the slave trade. He was also a president at various times of the Colston Society, the Dolphin Society and the Anchor Society.

Because of his political influence in the city, Thomas Daniel earned himself the nickname of the ‘King of Bristol’. His business interests included sugar importing and sugar brokering, iron importing, banking and investing in Bedminster coal mines and the Bristol Copper Company. He was a leading investor in the Bristol Dock Company as the official representative of the SMV, becoming the warden of that organisation in 1805. He owned and part-owned approximately 25 ships which sailed between Bristol and Barbados.

Continuing in his role his father had carved out as a creditor, the firm of Thomas Daniel and Sons became dominant mortgage providers for planters in Barbados and the Windward Islands.

Like many of the mercantile elites in Bristol, he ensured the safeguarding of his West India interests through his presidency of various societies (including the Colston Society) among other roles to ensure his place in wider Bristol political society.

After the Act of Abolition in 1833 was passed, compensating slave owners for the loss of their ‘property’, Thomas Daniel and his brother made over 52 claims for 6,900 enslaved people and 27 of these claims were successful.

The successful claims were for approximately 4,424 people including my grandfather’s grandfather. His name was John Isaac and I understand that he was around five years old at the time. The claims may also have included his parents.

Thomas Daniel and his brother John received over £130,000 in compensation which was divided between them, with Thomas Daniel receiving compensation for a further 200 enslaved people that were personally ascribed to him. This made him one of the largest claimants of compensation money given to British slave owners, the third largest in the country.

There are several ways of working out inflation rates to compare what the figure equates to today – in terms of purchasing power the figure allotted to Thomas would amount to over £7 million today – however the real figure of compensation to get one’s head around is that the total amount of the “bail out” to slave owners of £20 million constituted approximately 40 per cent of the GDP at that time.

It is too traumatising for me to think of the individual sum that was configured for John Isaac and each and every other enslaved human being. However, it is important to understand the “apprenticeship” scheme that accompanied the compensation which meant that formerly enslaved people who had been given their so-called freedom were then required to continue to work for free for a further four to six years (depending on the class of worker) before being entirely free. Anyone under the age of eight was emancipated immediately but John Isaac’s parents, if they were still alive, would have remained enslaved under the apprenticeship scheme.

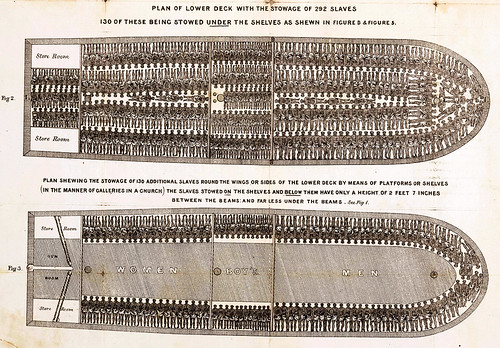

Professor Hilary Beckles, Vice Chancellor of the University of the West Indies, describes Barbados as the most ruthlessly colonised country with it taking, at one point, on average seven years from transportation to the colony for enslaved people to be worked to death.

British tax-payers including the British African/Caribbean diaspora who were invited to work in post war Britain, also contributed to repaying the interest on the government loan (raised by the Rothschild Syndicate) obtained to pay the compensation through their taxes until 2015, This means that my father, his brothers, his children including me, and his children’s children, including my own nephews and nieces, would have contributed towards the compensation for the ‘freedom’ of his great-grandfather, my great, great grandfather.

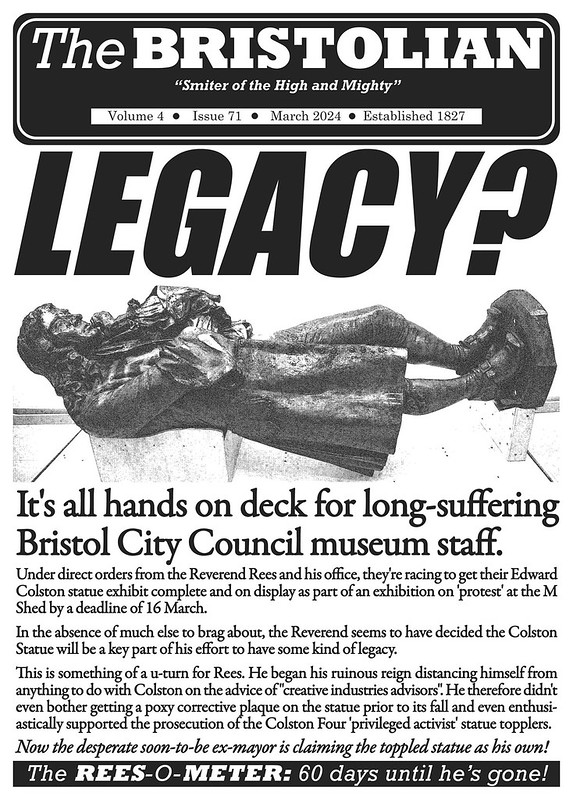

When I heard that the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston had been toppled I felt a huge wave of relief. The world had witnessed the public execution of George Floyd and we had finally arrived at a place in history where people would no longer tolerate the continuing dehumanisation of black people.

I am aware that George Floyd’s great, great grandfather was an enslaved man, like my own. He or his forebears would have been transported to America on a slave ship, such as those occupied by the Royal African Company under Edward Colston. In the words of Malcolm X, referring to the unassuming rock said to mark the point of arrival of European settlers in what we now know to be America, ‘we did not land on Plymouth Rock, the rock was landed on us’.

The ancestors of George Floyd did not choose to go to America, they were taken there by force and their descendants have lived with the racist legacy of that trade.

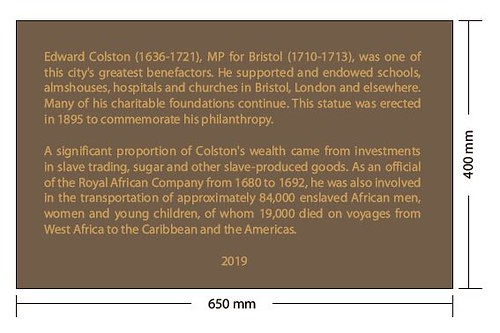

The fact that the statue of a slave trader had remained up for so long, and without contextualisation, was in my view profoundly shameful. I am aware the Colston Society was disbanded after the statue came down. I do not believe that would have happened otherwise.

The statue being felled and dragged through the streets of Bristol to a watery grave centred the global conversation on the birthing role Britain played in the transatlantic slave trade. It has not only removed a statue that caused a huge amount of hurt to the community, it has also served to educate people about the role and about Colston himself.”

The trial will continue tomorrow if The Bristol Recorder and the Crown Prosecutor are shameless enough to turn up and continue with this morally repugnant fiasco masquerading as justice.